Bright Simons: Will Pan African Payments Settlement System save AfCFTA?

On January 14, 2022, the Pan African Payments Settlement System (PAPSS) was launched in Accra. In addition to six West African central banks, mainly from the mainly Anglophone WAMZ region, Afreximbank (the lead sponsor) and the AfCFTA Secretariat, a number of important governments and corporations graced the event to signal their support.

PAPSS is considered the fourth of five key pillars supporting the effective rollout of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), a treaty signed by 54 of Africa’s 55 countries (excepting Eritrea) and ratified by 41 of them so far with the goal of creating the long awaited common market across the continent.

AfCFTA is momentous even by global standards. It is the world’s largest trade area by participating members, even if other trading blocs like RCEP and the EU have greater weight by GDP. But Africa’s integration and unity has had so many false starts that AfCFTA has been greeted by much apprehension since it was signed in 2018 and even after it went live in January 2021. Take the famous “open skies agreement” which is now two decades deep into oblivion.

Mindful of this context, many observers have been looking for “what is different this time around”, and some have fallen for tech, financial technology in particular, which is where PAPSS comes in.

PAPSS’ key promise as a saviour of AfCFTA is deliciously straightforward, not only will it save the continent $5 billion in fees that currently goes offshore, it will also help AfCFTA take trade among African countries, presently estimated at 17%, to as much as ~22% by 2040, generating additional value of about $70 billion.

Indeed, if forces like tech push liberalisation even harder, the proportion of Africa’s trade that stays within the continent could exceed 25%. A sensible ambition when you consider that nearly 70% of European trade happens within the EU and 60% of Asian trade within Asia. PAPSS will do this by enabling African traders to pay for goods in other African countries using their own domestic currency whilst the seller gets paid in their local currency as well.

Like every big idea in Africa, PAPSS has been tried in different forms and guises over the years in Africa. A number of Africa’s major regional trading blocs have something similar. In the Southern part of the continent, SADC has a unified payment system called SADC-RTGS (previously, SIRESS) patronised by 14 of its 16 countries (with transactional value exceeding $450 billion by March 2020).

The East African bloc has EAPS and both major Francophone-dominated zones – WAEMU (West Africa) and CEMAC (Central Africa) – have unified, multi-country, cross-border payments systems as well. In fact, 30% of trade in the Francophone trading blocs happen in the regional CFA currency on the regional payment networks, such as CEMAC’s SYGMA, already.

So, apart from ratcheting up the scale, could PAPSS change the game much more radically? A lot would depend on a more rigorous definition of the problem it has set out to solve and a lot of strategic wizardry. Misunderstanding PAPSS’ true opportunity would lead to disappointments and confusion.

Some have dubbed PAPSS a SWIFT killer because of certain misconceptions about the promise to “save Africa” billions of dollars of fees which currently go overseas. But this is a complete misapprehension.

SWIFT is the global behemoth that enables banks to send secure transactions to each other authorising payments from sender to beneficiary. 11,500 out of the world’s 25,000 banks, of which about 1050 are in Africa, send 42 million such messages every day to 200 countries around the world. The actual fee per message is around 4 US cents ($0.04). This is hardly the driver of the 6.3% of sending amount that senders pay on average to transfer money from country to country or the $25 to $65 senders see on the telex advice when they wire money from their bank to a recipient in another country.

Those costs are driven by intermediary banks between theirs and the recipient’s, sometimes called “correspondent banks”. Because it is unlikely that the sender and the recipient would both have accounts in the same bank, especially for an overseas transaction, the only way to transfer money in the current global banking system is for the sender’s bank to look for another bank in which both they and the recipient bank have accounts. These would typically be big global banks since it would be ridiculous for each bank to hold accounts in thousands of banks around the world.

A few hundred global and regional banks are trusted enough to serve as bankers to other banks in order to facilitate these global payments. Occasionally however one finds that there is no intermediary bank that both sender and recipient banks share in common, necessitating the search for an intermediary between the intermediaries. Now, because each bank needs to be paid for their service in the chain, costs can rack up.

For that reason, the issue with enhancing payment flows and cutting costs is not really about the need for an African financial messaging service. In fact, the biggest of the existing regional payment networks, the SADC-RTGS, actually uses SWIFT for the messaging part of the process (as does the UK’s CHAPS network and many others around the world). In fact, the SWIFT charges in the transaction fee are lower than the SADC-RTGS charges.

In many respects, the framework and architecture for all cross-border payments draw on the standard Real-Time Gross Settlement (RTGS), which dates back to 1970 when its bare contours were set by the US Fedwire system. There are about four major companies around the world trusted by central banks and other major financial system actors to build these networks: Sweden’s CMA, the UK’s Logica, Swiss-South African Perago and Montran, an American firm.

The costs of implementing RTGS networks in countries and linking them together is far from prohibitive. In 2008, the African Development Bank (AfDB) provided a grant to the four West African countries outside the Francophone CFA area that had not built an RTGS network to build one and network them together to establish a common network. The project, undertaken by Sweden’s CMA and French-Tunisian firm, BFI (eight other contractors playing minor roles), cost about $36 million.

If there is a serious driver of cost in the African context, as far as the technology infrastructure itself is concerned, then it is primarily volumes and participants. African banking systems often have lower volumes of transactions than elsewhere, leading to a higher cost per unit transfer.

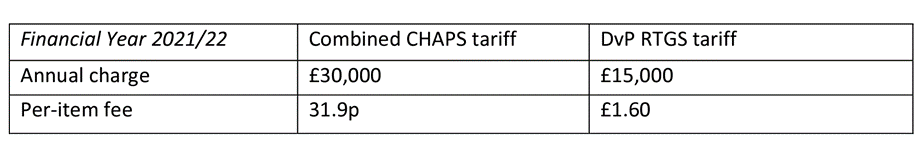

For example, take Liberia. Once the AfDB-funded RTGS platform went live, the country’s central bank needed to devise a formula to charge participants. Below is the breakdown it came up with the breakdown below.

It is clear from a even a cursory glance at the table that the primary cost driver here is firstly the number of participant banks sharing the capital costs, and how that will be passed through in fees to the end user. A fact clearly evidenced by the lower costs for similar services in the United Kingdom.

Apart from the somewhat trivial costs associated with SWIFT, its large volumes also provide a resource base that guarantees very robust infrastructure and high uptime availability.

In an analysis by the CEMAC Central Bank (BEAC) in 2017, it was shown that 80% of adverse incidents reported related to the region-specific network SYSTAC whilst transactions operated on the global SWIFT network registered only 5% of the reported incidents. Of these incidents, whilst 100% of the SWIFT ones were resolved, 60% of the SYSTAC incidents remained unresolved.

Not surprisingly, many of the major African banks have not been as enthusiastic as one would assume in promoting regional payment networks. Even the most successful regional payment networks can find this barrier daunting. Five years after launch, only 31% of banks in the SADC region had signed on to SIRESS (now SADC-RTGS) and nearly 60% of all traffic still bypassed it.

Messaging facilitation is thus not a significant source of new value to entice banks to a payment network. The real source of value, the ease and course of intermediation, is also the biggest driver of cost, partly through margins buildup and an even more critical factor, liquidity risk.

A proper understanding of the intermediation and liquidity issues also addresses another misconception around PAPSS: speed of payments.

It is not the inherent inefficiency of the SWIFT system itself that causes delays, contrary to some popular perceptions. In actual fact, the average time to settlement of 40% of all SWIFT transmissions is five minutes. Intermediary bank involvement drives this average up to 30 minutes for 50%, 6 hours for 75%, and 24 hours for 100% of all transactions on the network. Virtually, all sources of delay are due to errors during initiation, of which 34% are formatting related alone.

In 2017, SWIFT introduced a set of enhancements called the Global Payments Innovation (GPI) meant to reduce the value chain related challenges and errors that often gets blamed on it. Of the banks in Africa that have adopted it, transaction time for 70% of payments is within 5 minutes. Any extra delays are due to factors such as regulation (many African banks, for instance, run additional manual anti-money laundering and anti-fraud checks before crediting inbound remittances). The problem is that only 5% of African banks (less than 50 out of nearly 4500 GPI-adopting banks worldwide) have signed up to the strict service level commitments needed to activate GPI for their customers.

Without African banks themselves stepping up to the plate to improve intermediation, PAPSS by itself will not be able to transform the payments value chain and cut the costs, time and inconveniences that are currently in the way.

The closest thing to what PAPSS wants to create is the European Union’s TARGET system (more precisely, its TARGET2 incarnation), the principal outcome of the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA).

If one looks at the TARGET2 price list, almost all the cost drivers relate to the risks and value of liquidity facilitation (and also error management, but that is incidental):

When one steps into a bank branch in Kampala to make a transfer of about $500, the charge for an outward EAPS transfer (made on the regional network) is $11.5 and $21 for a SWIFT payment. If the user initiates the payment online, the cost drops to less than $6 regardless of method. Anything else that is added relates to the presence or otherwise of an intermediary bank. The total expense associated with the transaction thus relates much less to the means of issuing the payment instructions (the payment platform, properly speaking) and much more to the commercial forces within the interbank network.

As the Kenyan Central Bank (CBK) noted in its recent discussion paper on the prospect of launching a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), the East African Payment System has struggled primarily because of such commercial forces, in this case the burden on individual member banks to hold enough liquidity of the different currencies involved in a cross-border transaction. Indeed, it is primarily such liquidity issues that made adoption of RTGS so slow to begin with. Unlike the batch settlement method where banks net off how much they owe to each other due to the transfers that have occurred over the period, RTGS type systems require constant, or at least high frequency, settlement making smaller and weaker banks potential bottlenecks in the chain.

CBK muses in its CBDC paper whether cryptocurrency innovations can help mitigate these currency interconvertibility situation. PAPSS does not go the cryptocurrency route. Near as I can tell, the mighty balance sheet of Afreximbank is the gamechanger here. Afreximbank aspires to become the major intra-day credit provider for liquidity purposes that in many domestic RTGS systems, central banks tend to play. Would it do this for free or at a cost?

There is no doubt that the entire success of PAPSS turns on how masterfully Afreximbank can position itself as the credit facilitator of continental trade. The political economy challenges are of course formidable but the path is clear.

Even within regional monetary unions in the continent, political friction is constant. Recently, the CEMAC central bank purported to block a national switch in Cameroon for competing with the regional payment network.

Some have suggested that PAPSS could circumvent friction by simply interconnecting the regional platforms like EAPS, SYGMA and SADC-RTGS to each other. Doing that, however, will imply a completely different business model as PAPSS would then not be able to market directly to banks.

The fact though is that 96% of all Africa-bound payments originating in the East African Community (EAC) end up within East and Southern Africa. 92% of Africa-bound payments originating in Southern Africa stay in that region. In Anglophone West Africa (WAMZ), on the other hand, less than 40% of Africa-bound payments stay within the WAMZ. Not surprisingly, enthusiasm for PAPSS is currently strongest in WAMZ, where the central banks have signed the four foundational legal instruments underpinning PAPSS, and, till date, lukewarm elsewhere.

It is not too clear that the inter-regional payments systems integration value proposition is the strongest. Right now, there is significant room for improvement within the regional payment networks themselves. PAPSS can become the powerhouse for driving collaboration among those banks that really want to cut intermediation fees and enhance the liquidity profile for cross-border trade payments, regardless of where they may be on the continent. As the SWIFT GPI saga has demonstrated, payments transformation is purely ecosystemic and value chain dictated.

Some trends point to opportunity. Between 2013 and 2017, intra-African correspondent banks increased from 230 to 260 whilst the number of foreign correspondent banks willing to do business with African banks dropped significantly. It would just be a matter of time before smaller African banks are relying more on the bigger African banks to navigate the global banking arena.

With its growing financial muscle, strong relationship with the AfCFTA Secretariat, and through deeper alliances with the AfDB and Africa’s biggest banks, Afreximbank can reduce the costs of maintaining expensive global relationships for the continent’s smaller and mid-size banks who do much of the SME banking.

The real opportunity in payments revolution is not at the RTGS layer, which is by and large a solved problem. It is in the “open banking” layer, where much smaller players can connect across simplified connection pipes to introduce life-changing services beyond moving money from point a to point b. To do that though means solving the massive issues of liquidity, identity, cross-border KYC, and currency interconvertibility, all of which are long overdue for radical innovation.

To date, regional payment networks relying on traditional tools have not been able to do this. PAPSS has the opportunity to go to the banking associations and governments and offer radical new approaches to cost-cutting within existing regulatory jurisdictions and once they bite to architect a continental model based on well functioning units. Such a move would not make it a friend of many of the traditional incumbents, but nothing ventured nothing gained.

Source: Ghana News